|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The dissolution of Rievaulx (3/5)

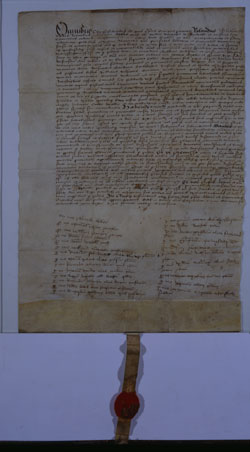

When Henry VIII issued the Act of Supremacy in 1534 and declared himself head of the Church in England, he embarked on a rigorous assessment of religious life in the country. He first ordered an evaluation of all the property belonging to the church in England and Wales, known as the Valor Ecclesiasticus, and then ordered that every religious house should be visited and a report compiled of any misconduct. A notorious twosome, Doctors Layton and Legh, were sent to investigate the religious houses in the North of England and were known for their surprise tactics, their pompous manner and rigorous questions. Layton and Legh probably arrived at Rievaulx towards the end of 1535. They would have subjected the monks to a gruelling visitation, quizzing them on all aspects of life, from their food and clothing, to the observance of the Rule of St Benedict, their attendance at the Divine Services, and the administration of hospitality and charity. At the end of their visit Layton and Legh would have left the community a set of injunctions and updated their notes with details of their findings which were then read out at parliament in 1536. They accused Richard Blith of Rievaulx of immorality with women and William Wordale of self-abuse.(5) These damning reports instigated the first Act of Suppression, which ordered the surrender of those houses whose annual income was under £200. Rievaulx escaped suppression. The first Act of Suppression, and a growing discontent with the situation in general, provoked uprisings in the North known as the Pilgrimage of Grace, which started in Lincolnshire. Abbot Blyton of Rievaulx seemingly kept his community away from the rebellion but his predecessor, Edward Kirkby, who had retired to Jervaulx, was implicated in the uprising and condemned to death, although later reprieved. The following year Layton and Legh returned to the North and were this time concerned to uncover evidence of what they called superstition, that is relics, miracles and cults which they claimed the abbeys used to dupe the people and profit financially. Following their visit to Rievaulx the commissioners reported that Aelred’s girdle was recommended to women in labour (as were ‘Mary’s girdles’ at Fountains and Jervaulx). The second wave of suppression followed and commissioners were sent to obtain the ‘voluntary surrender’ of each house using persuasion, coercion, or if need be, force. This time Rievaulx did not escape and on 3 December 1538 Abbot Blyton and his twenty-two monks gathered in Rievaulx’s chapter-house for the final time and surrendered their abbey to the royal commissioners. The abbey was valued at £227 10s 2d and had 102 servants. The community then disbanded and the abbey, with its home estates of Ryedale and Bilsdale, was granted to Earl Thomas Manners of Rutland who set about the destruction of the buildings. The earl clearly made a thorough good job of this, for less than half of the 72 buildings that once stood within the 92 acre precinct can now be traced.

However, five surviving documents, all compiled within the first year of the abbey’s dissolution, provide a remarkable insight into the layout and composition of Rievaulx’s precinct, and also the furnishings of the buildings, in the later Middle Ages.(6) A unique discovery has recently been made at Rievaulx – a stained glass red image of a red cockerel, some 10cm wide, that would have made a ‘satirical addition’ to the abbey’s main windows. This is the only complete image of an animal known to have survived the dissolution of the monasteries. The rest of Rievaulx’s stained glass was transported to London in 1539, where it was sold and the profits directed to the royal coffers. |