|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

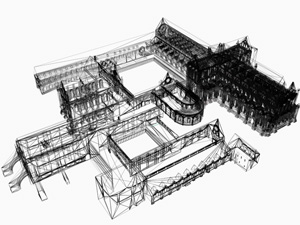

The layout of the church (3/8) The layout of the Cistercian church represented and reinforced distinctions within the monastery. A defining feature of the Cistercian Order was its incorporation of two communities. The abbey church was designed to accommodate both groups separately: the monks’ choir occupied the eastern part of the church, the lay-brothers’ was situated in the west. The two were divided by a large partition known as the rood screen. Further divisions separated the sick from the well and members of the community from outsiders. The twelfth-century church at Rievaulx was Romanesque in design and cruciform in shape. The aisled nave was divided into nine bays and extended over fifty metres in length. The north and south transepts (the sidearms) each had three chapels where ordained monks could pray and celebrate private masses. These were demolished during the fourteenth-century renovations and replaced with vaulted chapels and timber roofs; the insertion of new windows also brought greater light to this area. The square-ended presbytery occupied the east of the church. It was unaisled and had two bays. The presbytery was the focal point of the church and the holiest spot in the precinct for it was here that the High Altar stood, that the Mass was celebrated and Communion received. A light would have burned before the High Altar throughout the day and night, but the twelfth-century altar would otherwise have been simply adorned. By the sixteenth century the altar was more ornately decorated: the inventory taken at the time of the dissolution of Rievaulx mentions an image of Our Lady and gilt statutes.(3)

In the thirteenth century there was a major

remodelling of the east end of the abbey church. The short east

end of the Romanesque

presbytery was extended into a much more elaborate presbytery.

This was built in the Early English style, which was less severe

than the twelfth-century architecture. The new seven-aisled presbytery

was vaulted and three storeys high, which was quite unusual in

a Cistercian context. The extension of the presbytery meant that

there were now nine chapels and this provided more room for private

prayer as well as for lay burial – for example, the abbey’s

patron, John Ros (d. 1393)

and his wife, Maria, were buried south of the High Altar. More

importantly, the presbytery also provided

a fitting resting place for Aelred’s splendid gold

and silver shrine, which was translated here from the chapter-house.

It may, in fact, have been for this reason that the presbytery

was remodelled. This extension of the presbytery altered the basic structure of the church. With the crossing and sidearms now situated in the centre of the church rather than in the east end, the abbey was no longer cruciform in design. It also meant that Rievaulx’s church now extended over 105m in length and was the longest monastic church in England. |