|

|

You are here:

The Dissolution: the end of monastic life

at Roche

(1/1)

The Dissolution of the monasteries by Henry VIII

(1509-47), spelt the end of monasticism in England and Wales. The

king, declaring himself the head of the Church in England, embarked

on a thorough assessment of religious life in the country, allegedly

to uncover and suppress dissolute conditions; it was, however, the

need for money that underpinned these pious claims. Henry first

ordered an evaluation of all the property pertaining to the church

in England and Wales, a survey known as the Valor Ecclesiasticus.

Thereafter, he instructed that each religious house should be visited

and a report compiled of misconduct therein. The commissioners sent

to the North of England were Doctors Layton and Legh, an infamous

twosome renowned for their surprise tactics, their pompous manner

and rigorous questioning.

The commissioners probably arrived at Roche near the end of 1535,

and subjected the monks to a gruelling session of questioning, quizzing

them about their food and clothing, the observance of the Rule

of St Benedict, attendance at Divine

Services, the administration of hospitality and charity, and

if boys or women lay with them. The commissioners accused five monks

of Roche of sodomy and one, John Robinson, of treason. John denied

having spoken either in support of the pope or against the king,

but was imprisoned at York 1535-6; he is likely to have been the

monk from Roche whom Sir Francis Bigod saw in fetters at York Castle

in 1536.(1) John was eventually released

and was present at the surrender of his abbey in June 1538. On their

departure Layton and Legh would have left the monks a set of injunctions

and updated their notes with details of the visit.

The results of these first visitations, which were read out at parliament

in 1536, instigated the first Act of Suppression, that ordered the

surrender of those houses whose annual income was under £200.

Roche was at this time valued at £222 and escaped suppression.

The following year Layton and Legh visited the North once more and

were particularly concerned this time to discover evidence of what

they called superstition, namely, relics miracles and cults that,

they claimed, duped the people to bring the abbeys financial gain.

They accused the abbot and convent of Roche of having a pilgrimage

to venerate an image of the crucified Christ.

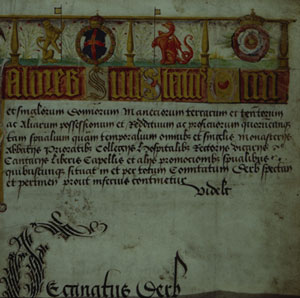

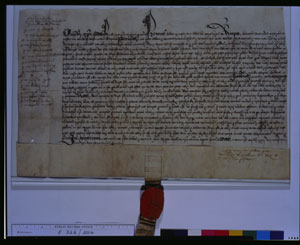

The second wave of suppression followed, and commissioners were

sent to obtain the ‘voluntary surrender’ of each house

using persuasion, coercion, or if need be, force. Abbot

Henry Cundall of Roche and his seventeen monks gathered in the

chapter-house at Roche for the last time on 23 June 1538, and signed

the surrender deed, sealing the fate of their abbey.(2)

The keys of Roche were then handed over to the commissioners and

an exhaustive inventory was taken of all the monks’ possessions

and livestock, which were then claimed as Crown property.(3)

Each monk was granted a pension, the precise amount depending on

his standing within the abbey. Every member of the community also

received a ‘reward’. Abbot Henry was given an additional

£30, as well as his books, a quarter of the abbey’s plate,

cattle, household items, a chalice, vestment and a portion of corn,

which was to be taken at his discretion. The other monks each received

half a year’s allowance, and every servant of the abbey was

given half a year’s wages.

Following the dispersal of the monks, the abbey buildings were

destroyed to ensure that the community would not attempt to

reconvene. The

monks’ goods were either plundered by the locals or sold -

a number of vestments and furnishings were bought by local church

wardens; it was said that the local carters used the monks’

service-books to patch up coverings on their wagons.(4)

The sheer speed with which the surrender and destruction of the

abbey was effected was quite remarkable, and a later commentator

showed incredulity that those who had only two days previously

condoned the monks’ spiritual work could now pilfer their

site.

<back>

<new section>

|