|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Mills, fisheries, turbaries, ponds, mineral rights, rights of passage (13/15) Cistercian monks fully exploited

their environment, and required a variety of holdings to support

a self-sufficient community. These included mills, fisheries, mining

rights, and turbaries (the right to cut turf) such as those at

Flotmanby and Mulethorpe. Mills The Cistercian Order prohibited its abbeys to receive revenues from mills, since this ran counter to its ideal that the monks should live by the sweat of their own brows and not that of others. Whilst communities could have mills for their own use, they were not to profit from these by collecting ‘multure’, the tax paid by those who were compelled to use the mill to grind their corn. Rievaulx certainly owned mills – an early record is the bishop of Durham’s grant of a mill in Crosby in 1152; a later example is a mill in Fryton, called ‘Poketo’, which was given to the community in 1222 by Hugh de Flammeville and was later leased to the nearby canons of Newburgh for the yearly rent of two marks.(41) Although it is nowhere explicit, it is likely that in some cases these mills did not simply serve the monks but provided the Rievaulx community with income.(42) The monks of Roche, near Maltby, had a windmill in Todwick, where locals had to pay a sum of money (multure) to grind their corn. This was clearly the cause of considerable resentment and in 1329, in a show of hostility, a group of embittered locals broke the abbey’s windmill here. Fishing rights

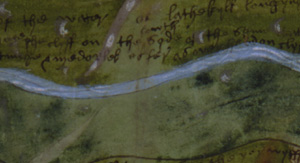

Fish was an important part of the monastic diet, especially on feast days and festive periods such as Advent and Lent, when the use of animal fat, eggs, milk and milk products was either prohibited or restricted. Fisheries were therefore an extremely valuable possession. In the late twelfth century Rievaulx acquired a number of these along the River Tees at places such as Newsham, Girsby and Normanby, and also at Scarborough, on the Yorkshire coast.(43) A grant of fishing rights might include permission to fish in the area, free movement of passage for the community’s boats, the right to build a fishpond or to take stones and turf for the upkeep and repair of the fisheries – such was the case at Newsham, near Yarm. It might also include a house where the lay-brothers could stay, and where fish could be stored, dried and salted.(44) The abbey’s fishery at Girsby was at the centre of a dispute in 1302, when the abbot of Rievaulx accused John Conyers and other of breaking his weir here and taking his nets.(45)

|