|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

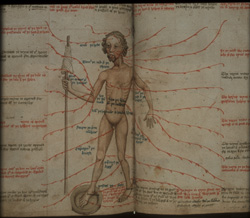

Glossary Bloodletting Bloodletting was a preventative and restorative treatment frequently administered during the Middle Ages. It was thought to restore balance to the body, to sharpen the senses and clear the brain; it was also believed to produce a musical voice, to promote longevity and quench sexual desire. Bloodletting in Cistercian abbeys, as in other religious houses, was a routine part of life. As a matter of course monks were bled several times a year, to keep them in optimum health; those who were ill might then receive extra bleedings to restore them to health. The monks were bloodlet in batches at least four times a year – February, April, June and September. There was to be no bloodletting at harvest, when everyone was needed to help in the fields, or at feasts when the entire community was expected to participate in all the services. The process

The bloodletting took place in the warming-house, usually in the late morning or early afternoon. A fire was lit in preparation and the monk could have a bite to eat in the refectory before undergoing the procedure; he would certainly need this extra sustenance for the monk was drained to the point of unconsciousness and might lose up to four pints of blood. This weakened him considerably and he required time to recuperate. In the twelfth century this recovery time was spent in the dormitory, cloister and chapter-house, but from the early thirteenth century the monk rested in the infirmary where he enjoyed a more relaxed diet and relief from the daily round of work and liturgical offices. During this recovery time, the monk did not participate in the chants; nor did he read. Any monk who held an office (obedientiary) was not expected to carry out any of his duties; his deputy filled in. This exemption did not, however, apply to the main office-bearers, namely, the prior, sacrist, cellarer and novice-master. On the third day after the bloodletting, the monk joined the rest of the community for some of the Offices and might read in the cloister; on the fourth day he was expected to play a full part in the daily life, although he did not necessarily engage in manual labour. |

|||