|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

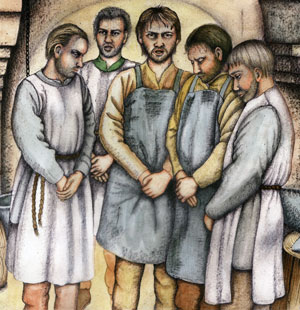

The decline of the lay-brotherhood (6/14)

The lay-brotherhood had its heyday in the mid-twelfth century, and at this time most abbeys had more lay-brothers than monks. During Aelred’s abbacy at Rievaulx there were about 140 monks and 240 lay-brothers and on feast days, when all the lay-brothers congregated in the church to celebrate the Hours, the church was crowded with the brethren ‘like bees in a hive’, making movement of any kind virtually impossible.(8) By the end of the twelfth century there were signs of decline. Reports of misconduct increased – both cases of individual disobedience and violence, and riots. An interesting example is that of William Acton, a lay-brother of Rievaulx Abbey in Yorkshire who, in 1279, claimed he was a leper, stabbed a monk of the house who was examining him and promptly fled into the woods with two monks of the abbey hot at his heels who subsequently caught William and beat him to death.(9)

A number of group uprisings were triggered by the prohibition of ale at the granges. The abbot of Margam’s banning of ale in 1206 incited the lay-brothers of the abbey to retaliate. They pulled the cellarer from his horse and proceeded to attack both him and the abbot, whom they then pursued for several miles. To cap it all off they barricaded themselves inside the monks’ dormitory and refused to give the monks any food.(10) The decline of the lay-brothers was also accelerated by external conditions. The demise of the manorial system of farming in the twelfth century had meant that a number of peasants were on the move seeking work and security. Membership of the Cistercian lay-brotherhood was seen by some as an attractive proposition. The disappearance of the manorial system and serfdom in the thirteenth century brought changes that augmented the demise of the lay-brotherhood. Peasants were now lease-holders and the Cistercian abbeys were, if anything, seen now as the competition rather than an alternative. The Black Death in the fourteenth century badly reduced their numbers, which never recovered. By the time of the Dissolution most abbeys had only a handful of lay-brothers. |