|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

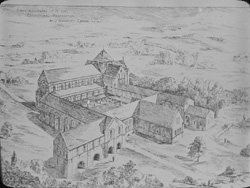

Kirkstall Abbey: the precinct

Kirkstall is one of the most complete sets of Cistercian ruins in the country. Following the surrender of the abbey in 1539 most of the buildings remained standing and the site did not suffer the destruction and plundering that occurred elsewhere, such as at Roche. Over the years, however, neglect, weathering and the growth of vegetation led to the partial collapse of the crossing tower in 1779 and the southern part of the dormitory in 1886. From the late eighteenth century the main thoroughfare to Leeds actually ran through the nave of the church; in 1827 the road was redirected and still bisects the site. The precinct at Kirkstall covered some forty acres and was bounded on the north, west and east by a stone wall, parts of which remain to the SE of the abbey; the River Aire formed a natural boundary on the south side. Entrance to the site was restricted and access was via the great gatehouse that stood to the north of the abbey, but which no longer survives. From here a lane ran some 300 metres to the inner gatehouse that now houses the abbey museum. A Cistercian abbey was a self-sufficient unit, and although agricultural and industrial work was carried out beyond the precinct, there was much activity within the abbey walls. The outer court in particular was a hive of industry. Situated to the north and west of the site it housed most of the abbey’s workshops and farm buildings. More domestic buildings such as the bakehouse and brewhouse, as well as the guesthouse, were located in the inner court, which stood to the north and east of the church. Two cobbled roads crossed the western side of the inner court. One road ran from the abbey to the outer court and probably led to the granaries and a malt house; recent excavations show that it was heavily patched and used by wagons and carts. Excavation reveals that the second road, which ran from the inner gatehouse to the church, was finely cobbled with no evidence of wheel marks. This was probably used by pedestrians and horses. The church and cloister stood at the heart of the precinct, sheltered from noise and activity. This area was essentially restricted to the monks and it was here that the buildings necessary for their daily life were situated, principally, the church, chapter-house, dormitory and refectory. The monks could access all these buildings without leaving the cloister. |