|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

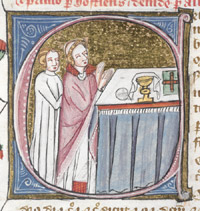

Glossary Mass The celebration of the Eucharist. Although the Rule of St Benedict includes no prescriptions for the daily high mass, this became an integral part of the monastic day. Cluny celebrated two or three conventual masses daily, but the Cistercians, who advocated simplicity and brevity, reduced this to one. A second ‘low’ mass was soon introduced on Sundays and feast days, and there were further additions during the twelfth century, including a daily mass for the dead (for deceased members of the community and ‘familiars’ ) and for the Virgin and benefactors. It was conceded that in times of crisis a mass for special needs might replace the conventual mass, and in 1194 the General Chapter ordered that prayers be said for the recovery of the Holy Land. (1) In addition to corporate masses, private masses were said by monk-priests at side altars, and specific times were set aside for this purpose.(2) The priest faced northwards and was assisted by two witnesses - a cleric who ministered to him and a layman who served the water and lit the candles at the consecration.(3) The daily celebration of private masses was not obligatory, but was generally observed and was indeed necessary with communities receiving a growing number of requests from donors for foundation masses. These could be lucrative, for the monks might acquire considerable gifts in return for their spiritual services; however the practice became increasingly onerous and from 1192 all foundation masses required the General Chapter’s approval.(4) Those who served communion to the monks might themselves receive communion at private masses, a measure that was surely intended to minimise problems created by a large community.(5) The daily conventual mass was celebrated by all choir monks. Officials, such as the porter, were excused on account of their work, but on feasts of two masses they were relieved of their post by a deputy and free to join the choir for the first mass that was celebrated after Prime.(6) On normal work-days the lay-brothers did not attend mass, although on Sundays and feast days they, and the brethren who worked on the granges, celebrated both masses in the church, and indeed participated in the full liturgical office. On feast days when they worked, the lay-brothers only attended the first conventual mass, but their presence was also expected at all burial masses. (7) The procedure for mass was defined by the simplicity

of its ritual - even with subsequent modifications. Like each of

the canonical hours, it began

with the Lord’s prayer and the sign of the Cross, which was followed

by an abbreviated version of the Confiteor, rather than the

customary Judica (Psalm 42). A priest acted as deacon, but

wore the stole around his neck as a priest

and not, as a deacon, across his shoulder. The celebrant was the

monk appointed as priest for the week, and it was his duty to sing

the oration until the oratory, where the altar was censed; this

was one of the few times that the Cistercians permitted the use

of incense, which was otherwise considered a luxurious and unnecessary

expense.(8) Other parts were sung by the

servers and the choir. The Gloria was intoned at the epistle

side of the altar, the Creed at the gospel side. At the beginning

of the Collect or Gloria the chalice was prepared;

it was not covered by vellum or a pall, but

by a corner of the corporal that was folded over for protection.

During the canon of the mass the celebrant broke the Host

(which was made of pure wheat)(9) in three

- two large pieces and a smaller piece that was dropped into the

chalice. Initially the sacrament was not elevated and the community

did not genuflect. The Cistercian statutes first prescribed that

the host be elevated in 1152 and the chalice in 1444; from 1210

it was decreed that candles might be raised during the elevation

to enable those in the choir to have a better view, and the lesser

bell rung so that all who heard it could genuflect and pray.(10)

The Pax (the Kiss of Peace) which followed,

was only given to those who were about to receive communion.(11)

|